Thursday was our last day of surgery. I knew it was coming, but it took me by surprise nonetheless. It all happened so fast. Empty bags filled back up; beds were stripped down; once lively rooms became quiet. It was all becoming a memory right before my eyes. I thought, No, don’t go. Please stay. Unfortunately, sometimes when you finally have time to sit down and have a cup of coffee with your experience, it has already gone. Such is life.

The team performed 65 surgeries on 49 people. Some of the procedures were big, some were small, but they all made a huge difference.

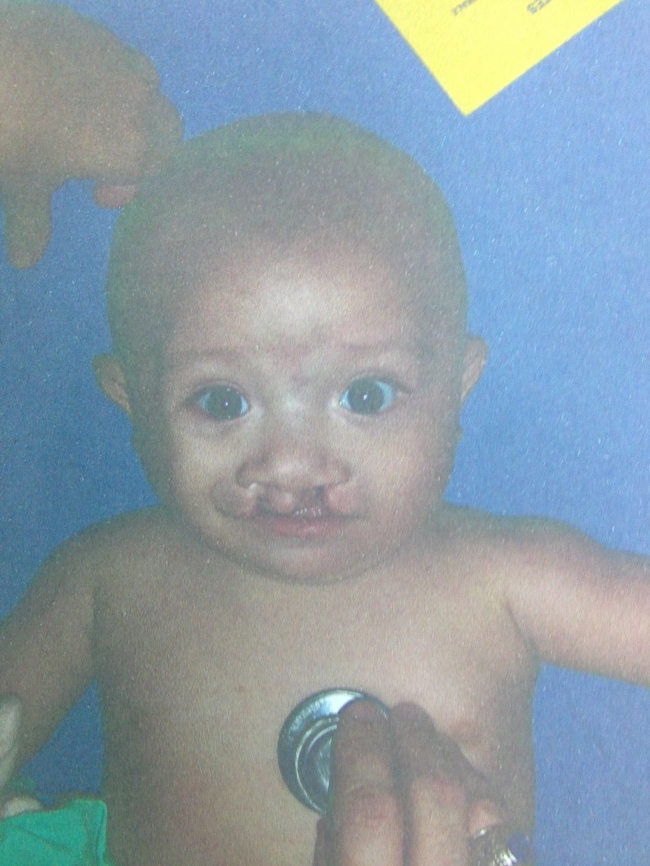

The last patient of the mission was a five-month old boy named Mateo, who had two procedures. First, I watched Dr. Leary place tubes in Mateo’s ears. It was a simple surgery that I found fascinating. Dr. Leary let me look into the microscope where I saw the small cut he made. Then he placed a tiny, blue, bobbin-shaped “tube” into the incision. He did this in both ears. The tubes will help normalize the air pressure in the ears, reducing the risk of infection, which had been a problem for Mateo. Even if he does get another ear infection, the tubes will help drain the fluids and minimize discomfort. The tubes are not permanent—they will fall out on their own in about six to nine months. Above: Dr. Leary putting in Mateo’s ear tubes.

Above: Dr. Leary putting in Mateo’s ear tubes.

Then the table was turned and Dr. Lima began a bilateral cleft repair.

***********************************************************************

Let me inject a little “sidebar” information here, a “did you know” section about cleft lip/palate.

• There is a higher incidence of cleft lip/palate in Hispanic and Asian populations, followed by Caucasians, then people of African descent.

• 60 percent of cleft lips are on the left side, 30 percent are on the right and 10 percent are bilateral (both sides).

• Cleft lip/palate is slightly more common in boys than girls.

• Cleft lip/palate is most commonly caused by a combination of a genetic predisposition (a gene that is slightly dysfunctional) and an environmental stimulus—things like anti-seizure medicine, alcohol/drug use, and smoking. In a minority of families, orofacial clefting is hereditary, usuallly associated with a syndrome (multiple related anomalies).

***********************************************************************

Dr. Harshbarger approved Dr. Lima’s markings, and then with painstaking precision, she cut and stitched flaps of muscle and skin. About two and a half hours later, Mateo had a perfect looking little baby face. He was carried to the recovery room where a cluster of caring nurses converged on him, checking vitals, and getting him ready to be back in the arms of his family. Mateo was one of the cutest babies I have ever seen and I couldn’t help but cry a little. This swelling of my heart sensation became a familiar feeling on the trip.

Above: Mateo before his surgery

Above: Mateo before his surgery

Above: Scrub tech, Steve Miley, and Drs. Lima and Harshbarger working on Mateo.

Above: Scrub tech, Steve Miley, and Drs. Lima and Harshbarger working on Mateo.

Above: Nurse Amber presenting baby Mateo to mother right after surgery.

Above: Nurse Amber presenting baby Mateo to mother right after surgery.

Above: Baby Mateo with proud Papa.

Above: Baby Mateo with proud Papa.

The day ended with the leaders of the military hospital and the Rotarians thanking us for our service. We were all awarded with commemorative certificates, papusas aplenty, and live marimba music. The mood was festive and fun.

FUN FRIDAY

Friday was the last full day, our day of rest, a chance to see more of El Salvador than the five-mile stretch between hotel and hospital. There were several excursions to choose from—beach and boat outing, zip-line fun, dune buggy tour…. Many of us chose the dune buggies. I enjoyed a window seat in the air-conditioned bus, which allowed for perfect viewing of the Salvadoran landscape. In the city section of our drive, I noticed men with shotguns stood guard at many of the doors, and there was a generous use of ugly, coiled razor wire on almost every building. Most of it, I learned, had a 22V electrical wire running through it. This was obviously not an aesthetic choice.

Things became more picturesque as we moved through the coffee covered hills. Coffee is El Salvador’s primary export. Kids of both the animal and human kind walked alongside the road, amongst chickens and dogs. My feelings changed depending on what caught my eye. Emaciated dog: sad. Laughing children: happy. Quaint adobe buildings: curious and nostalgic. Food stands: hungry. Women carrying big baskets on their heads: impressed. The dune buggies were much more fun than I expected. Though the revving and speeding of our motorized vehicles through Apaneca, an old quaint town built in the 1600s and rebuilt in the 1800s after an earthquake, seemed a little imposing, the people seemed happy to see us.

Above: Me and Ray in our buggy

Above: Me and Ray in our buggy

Above: Kids getting out of school.

Above: Kids getting out of school.

We all met in the lobby the next morning and our transition back to the unreal “real” world began. I can see why people choose to do these mission trips again and again. It’s a unique experience. A band of brothers and sisters in the trenches together, making good things happen. Yet the bond forged in common cause loosens with every step toward the responsibilities of our day-to-day lives. We separate in different directions, but for a moment in time, we shared something very special. I’ll never forget them. Breaking up is hard to do.

AN END TO A BEGINNING

I don’t feel like people lesser than us were served; we served each other. It worked both ways, in equal parts. We all carry burdens, we just wear those burdens differently. People are tough; we’re a resilient group. A big smile and a hardy laugh can happen in the most abject of places; just as tears can flood the floor of the gilded cage that many of us live in. It’s the freedom of choice that makes the gilded cage the place you want to be—just be sure to keep that door open to opportunity. If I had any advice to give those of you yet to leave the safety of your gold surroundings, it would be this: Fly free, my friends, and let the world amaze you.