As you know already (because you have been reading every single one of these blogs, right?), we have arrived in El Salvador and to the crux of this mission. Let the real blogging begin!

I’ve already told you how important it is to be on time here. You will get left behind. That’s no joke. It doesn’t matter who you are. Knowing this, my husband tells me he’ll meet me downstairs (smart man). I tidy the room so the maids don’t have to do too much (is that weird?), then I rush to what has to be the slowest elevator known to man. It takes too long. I run down the stairs in a panicky mess, whip out my iPhone—it’s 7:29 when I board the bus. Yes! I made it, with a minute to spare. I meant it when I said I am always “barely” on time. Two other volunteers weren’t so lucky. At 7:30, Cullington commands the driver to start the engine and off we go to what will turn out to be one of the most memorable days of my life.

The military hospital is a ten-minute ride from our hotel. A crowd of patients are waiting to be seen, but we are escorted upstairs to get briefed on procedures and protocols before we can screen them. A picture is worth a thousand words, so I’m going to save us all some time and infuse this blog with some of the photos I took with my iPhone today. Mostly because I don’t think I can come up with the words that will do this experience justice.

Here’s how it works:

The patients are organized by age and area of concern—cleft lips, cleft palates, hands and “other,” which includes things like palatal fistulas, ear tubes, orthodontics, and craniofacial anomalies such as hemifacial microsomia (one side of the face doesn’t develop as well as the other in utero).

Then the doctors move down the line and select the patients who are good surgical candidates. Here Dr. Cullington selects a patient to go to the next level: medical clearance in the triage room.

Drs. Leary, Harshbarger and Lima examine patient in the screening line.

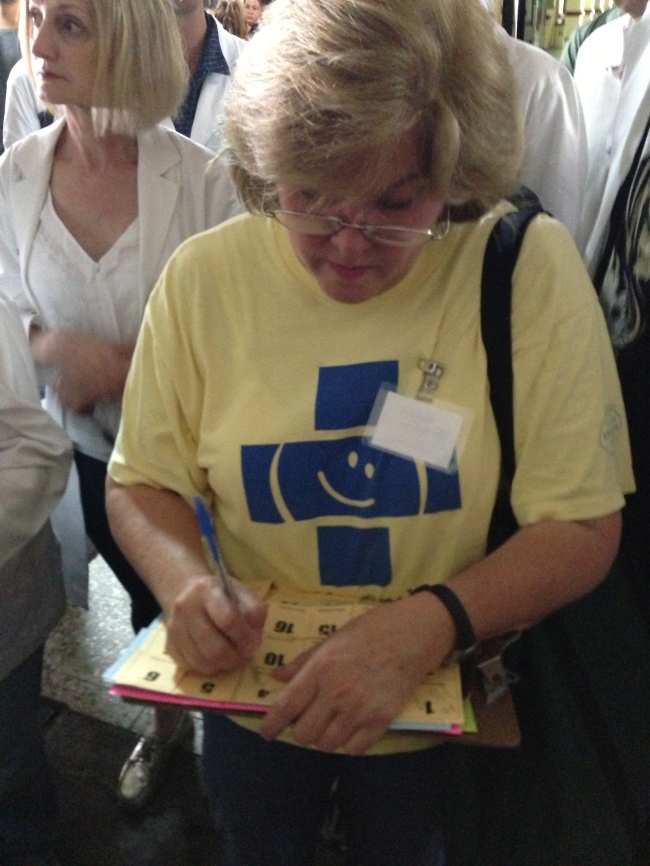

Kendyl gives each patient who is selected a ticket to go to the triage room, where a medical history is taken, airways are checked, and the general health of the patient is determined.

Here Drs. Leary and Playfair examine patients in the triage room.

We saw some adorable children and my heart swelled with love for every single one of them:

Children with cleft lip/palate need attention at many points during their development, from infancy through teen years. One of the exciting things happening with the trip this year is the addition of more services along the continuum of cleft care. This is the first time Austin Smiles is doing jaw surgery. Many kids with cleft lip/palate will have decreased growth of the upper jaw, related to scarring from previous surgeries, and intrinsic growth disturbances. The end result is a mismatch (often severe) of the teeth and jaw position. Corrective jaw surgery can align the jaw and teeth position to create a normal bite. Other great benefits include better speech, improved breathing, and facial harmony.

Drs. Harshbarger and Wadwa examining jaw patient.

Adorable eight-year old cleft patient, Maria, arrives with her grandparents.

Dr. Lima examines patient.

Patient with multiple craniofacial anomalies that have constricted her upper airways so she requires a tracheostomy.

There are so many more patient and volunteer stories that have yet to be told. I just can’t get it all in one blog post. Tomorrow is another day—until then, stay tuned.